“We are taking you behind the curtains of the production of an artist’s book,” said Christine Dixie of the Department of Fine Arts at Rhodes University. “In this seminar we unpack the ways in which words and images are brought together to disrupt traditional ‘reading’, a disruption that is echoed in the disruption brought into our lives by COVID-19.”

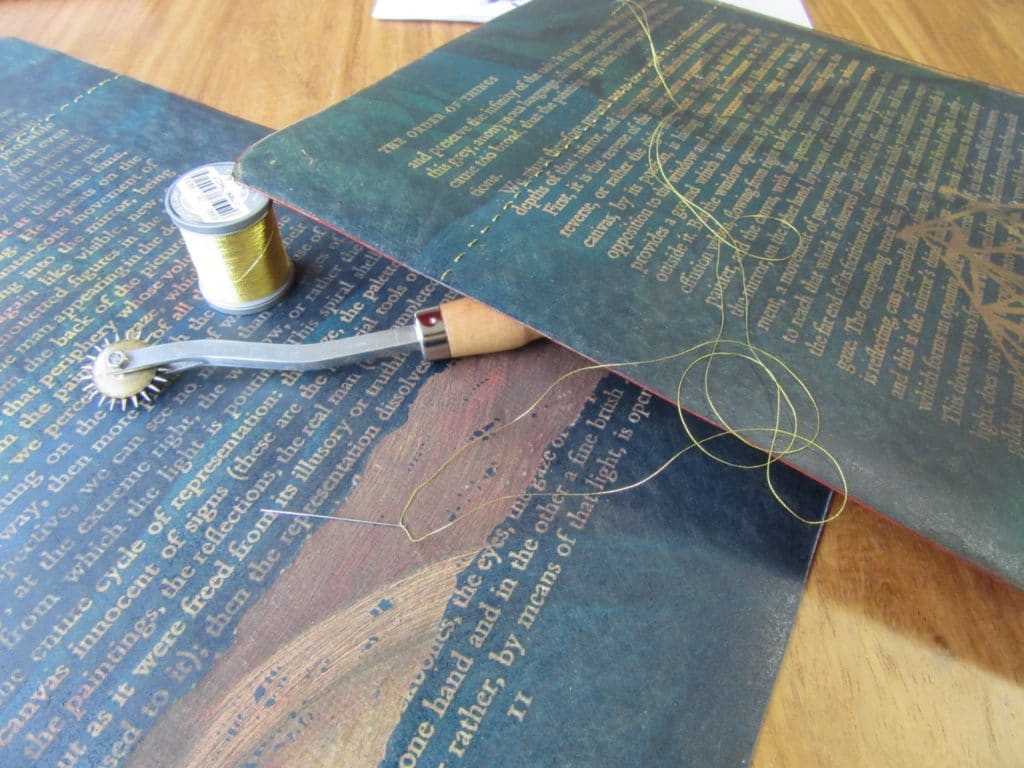

In their very interactive and hands-on seminar, Dixie and Heléne van Aswegen of the Department of Visual Arts at Stellenbosch University, explained the complex technical processes that go into the production of an artist’s book as well as the inspiration and meanings behind their current project Blueprint for the Disorder of Things.

The project is Dixie’s response to the pandemic and was conceived and partially executed in her living room during lockdown – “The pandemic has allowed us to change how we do things to our advantage,” she laughed. It forms part of an ongoing project entitled To Be King.

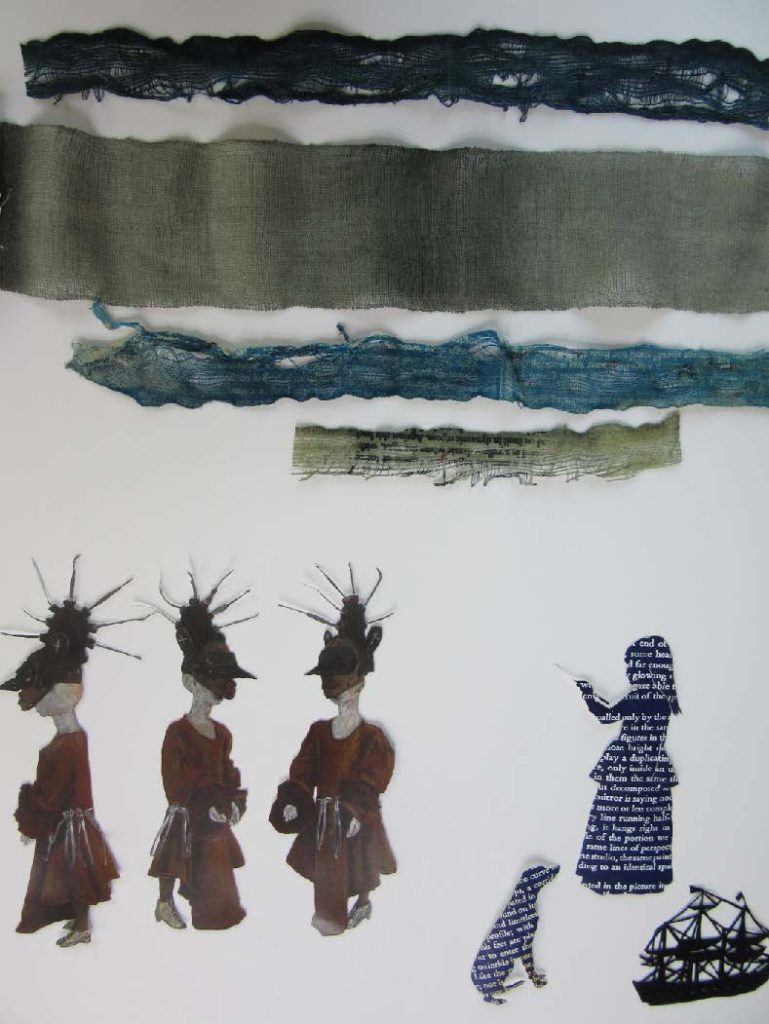

“The overarching framework of the project is informed by a post-colonial reinterpretation of the painting Las Meninas by Velasquez and the essay Las Meninas written in French by philosopher Foucault in 1966 and translated into English in 1970 as the first chapter of his seminal work The Order of Things.”

Las Meninas was painted by Diego Velázquez in 1656 and depicts a scene in the Court of Phillip IV during the Spanish Golden Age. It was seen as a hugely revolutionary work due to its complex depiction of reality and illusion, and is one of the most widely analysed works in Western painting.

“I’m fascinated by the painting which is set in the Court of Phillip IV of Spain showing the King and Queen and their daughter, the Princess. It’s a play of gazes – both within the painting by means of a mirror image but also with the viewer,” said Dixie.

“In his essay Foucault saw it as looking at relationships of power – with the King controlling how things are seen and who sees what,” she continued. “The Foucault text used the painting to talk about philosophy not art which again caused a big reaction.”

“I have worked with both the painting and the chapter in Foucault’s book, given it a specific location in the Eastern Cape, and attempted a post-colonial interpretation of the original,” she added.

She explained that her work comprises two figures that interact – the Princess from the original and a Plague Doctor, an ominous, hybrid figure which combines African masks, the traditional plague mask and medical instruments. The figures interact throughout with the Princess fading as the Plague Doctor becomes more dominant. There is also a silent witness figure in the form of a dog which Dixie changed from an Alsation type in the original painting to a Rhodesian Ridgeback. There is also a recurring bandage motif which appears in a lot of her work and points to wounding.

“The aim is to provide a sense of disorder and disruption. Things falling apart, a particular order that is thrown out. The questioning and disruption of language in complicated times. Things which are there but hidden beneath overlaid fragments. A depiction of life at the moment within the pandemic.”

The next step is to create an artist’s book as a medium through which to examine the spaces between vision and language, image and text, the two- and three-dimensional.

Van Aswegen explained that artists’ books are artworks in the form of a book. They are usually published as one-off or small editions and are generally interactive, portable and easily shared. Some completely challenge the conventional book format and become sculptural objects in their own right.

“Handmade artist books are about physical interaction,” she said. “They are not artwork on a wall.”

“They aim to create a unique space to convey meaning through the interaction of the viewer, or ‘reader’ as they traverse multiple spaces and through other senses such as touch and even smell. The matrices, the copper plates onto which the text is etched, have the potential to double as both an inscribed and reflective surface. This intrinsic quality suggests the viewers’ complicity in the narrative that unfolds.”

“It’s about deconstructing the idea of a book,” she continued, “what it is, its function, how you engage with it. The book as a culmination in itself. The materials become text, and the text becomes the carrier in a reversing of roles.”

“The field is vast and varied, and there are ongoing arguments about what it is and what it is not. It’s about breaking down our understanding of a book.”

She also highlighted the labour-intensive processes and how expensive such books are to produce.

“It’s a highly labour-intensive process with each project bringing unique challenges. In this project, for example, using double-sided pages is a technical challenge. Etching and embossing puts huge pressure on the paper – you therefore have to work by hand on the other side.”

“But the process is about ensuring that the material and conceptual components complement one another. Bringing in the personality and perspective of the artist.”

“It’s not about creating a pristine product which, in this case, adds to theme of the disorder of things,” she added. “We use visual ways of disrupting how one reads the text – through gaps and blocks.”

“There is a very small audience for such works in South Africa,” added Dixie, “and buyers are even smaller. The goal is to exhibit the work as a tactile, sculptural, three-dimensional object.”

“It’s our belief that this burgeoning genre has vast unexplored territories that require research and experimentation as it has the ability to transgress the boundaries between academic research and art making,” continued Dixie. “Artists’ books are becoming a revered medium with institutions such as MoMA, the Smithsonian and the New York Library. Locally, Wits Art Museum has followed suit by establishing a special division to house the vast collection of art patron Jack Ginsberg. Stellenbosch University is the only institution with a dedicated studio for the production of artists’ books. This was set up by Heléne van Aswegen and Prof. Keith Dietrich when the J.S. Gericke Library’s book restoration department closed in 2010. Located in the Visual Arts Department Building, the studio is used as a specialised workshop space to teach students as well as a production space for artists to create books in collaboration with van Aswegen.”

Michelle Galloway: Part-time media officer at STIAS

Photographs: Noloyiso Mtembu, Christine Dixie and Heléne van Aswegen