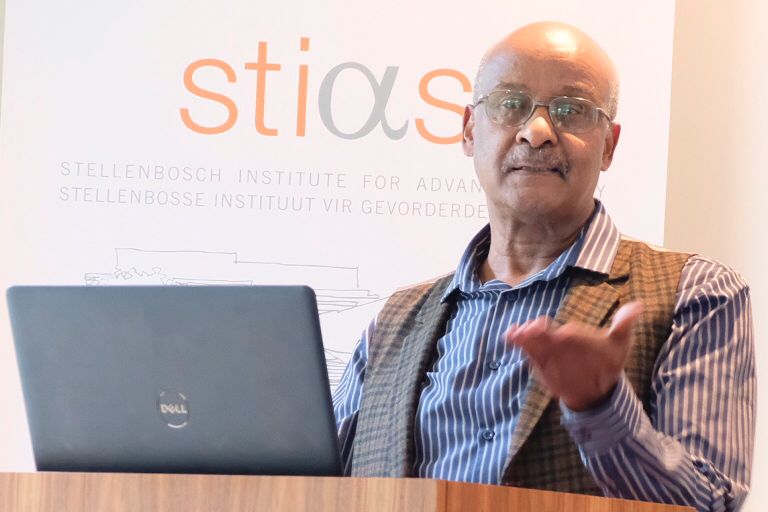

“On the surface, Ethiopian identity should be a given. It’s a country with a long history and an identity that is globally recognised,” said Bahru Zewde, Emeritus Professor of History at Addis Ababa University, Founding Fellow of the Ethiopian Academy of Sciences, Fellow of the African Academy of Sciences and STIAS fellow. “But, as its current predicament makes abundantly clear, the issue has forced the country to be delicately poised between renewal and disintegration. How did this come about?”

Zewde was presenting the second STIAS public webinar of the second semester of 2021. A leading scholar on Ethiopian history, Zewde’s major research interest has been Ethiopian intellectual history, resulting in two books: Pioneers of Change in Ethiopia: The Reformist Intellectuals of the Early Twentieth Century (2002) and The Quest for Socialist Utopia: The Ethiopian Student Movement c. 1960-1974 (2014). Other major publications in English include: A History of Modern Ethiopia 1855-1991 (second edition, 2001) and an anthology of his major articles, Society, State and History: Selected Essays. He was also a contributing author to National Identity and State Formation in Africa published by Polity Press this year and the outcome of a three-year research project initiated by STIAS under the leadership of Manuel Castells (Permanent Visiting Fellow) and Bernard Lategan (Founding Director).

Describing the issue and country as vast and complex with a contentious and violent history, Zewde said: “I’ve been batting with the question of identity in Ethiopia for nearly 20 years”.

“Ethnicity versus national identity is a global reality and often hotly contested,” he added. “There are many examples – Ireland, the Balkans, Catalonia and Basque in Spain, Cameroon, Nigeria, Rwanda and South Africa.”

“There are many critiques of ethnic identity because it is so often linked to violence. The challenge is in tempering ethnic and national identity.”

He also pointed to the many everyday examples of people with multiple identities and the challenges in accommodating this.

He described the literature as largely divided into primordialists and instrumentalists with “primordialists believing the issue is fixed and natural and has been here forever, and instrumentalists believing it is something that is created and therefore liable to manipulation”.

“Rwanda is probably the most obvious example of the invention of ethnic identities,” he said. “The Tutsi and Hutus were not recognised as distinct ethnic groupings until the Belgians came along and identified them specifically by the use of ID cards which, during the genocide, became their doom.”

‘I see Ethiopia as closer to the instrumentalist thesis. The identification of ethnic identities comes quite recently in its history.”

Zewde described Ethiopia as a country with at least two millennia of recorded history, a multi-ethnic ruling class and a tradition of ethnic interaction. “More than once, its people rallied to successfully resist external aggression.” He highlighted the Battle of Adwa in 1896 in which Ethiopian forces defeated the Italian invading force thwarting expansion of the colonial empire; Ethiopian resistance to the takeover by fascist Italy in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935 and to the ensuing occupation (1936-1941); the Ogaden War between Somalia and Ethiopia in 1977/78; and, the Eritrean-Ethiopian border conflict between 1998 and 2000. “In these conflicts Ethiopians fought as one,” he said.

Although there are two major ethnic groups – the Amhara and Oromo – Zewde argued that, historically, groups identified themselves more by region than ethnicity, and highlighted the high levels of ethnic interaction and integration and the existence of sporting, cultural and political leaders with more national than ethnic icon status.

Narrative of division

“The antithesis started to appear in the 1970s, with a narrative that gave primacy to its constituent nationalities,” he said. “It was accentuated by the emergence of ethno-nationalist liberation fronts.”

“I see ethnic identity as a development of the 1960s,” he continued. “After the 1960s there was thinking and organisation along ethnic and language lines, and more emphasis on group identity. This counter narrative of opposition and marginalisation of groups has been somewhat exaggerated.”

He indicated that the role of the student movement was very significant in the 1960s and 70s, explaining that the 1974 revolution which ousted Emperor Haile Selassie was initially spearheaded by students leading to the establishment of a Marxist-Leninist state under a military government. The Civil War ended in 1991 with the overthrow of the government by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front.

However, it was in the constitutional sphere that the narrative of ethnic division was strongly entrenched.

“The climax of this narrative was attained with the promulgation of the 1995 constitution that enshrined this primacy, to the extent of recognising the right of ‘nations, nationalities and peoples’ to self-determination, up to and including secession,” explained Zewde.

“The 1995 constitution had many positive aspects but also glaring anomalies. It showed a lack of knowledge about the country and ignorance of the interrelationships.”

“As the recent spate of ethnic conflicts all over the country has shown, a medicine that was ostensibly intended to cure a long-standing ailment is threatening to bleed the country to death.”

Zewde pointed out that although there have been attempts at promoting national unity and consensus through Flag Day and Ethiopian Millennium celebrations, and that current Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has attempted some revival of pan Ethiopianism and has established Peace and Reconciliation and Identity and Boundary Commissions, ethnic-based conflict is prevalent. “Although he has Oromo parentage, not all Oromo accept him. There has been resistance from Oromo nationalists as well as ongoing confrontation with the Tegray People’s Liberation Front.”

So what does Zewde see for the future or as a ‘synthesis’? “It’s still work in progress,” he said. “But, there is general consensus that the ill-fated constitution has to be revised substantially. While the federal arrangement is an inescapable reality, its ethnic element has to be attenuated significantly. Accommodating ethno-nationalist identity need not come at the expense of pan-Ethiopian identity. Above all, the promotion of democratic institutions is a sine qua non for the exercise of genuine federalism.”

“I believe political pluralism is more important than self-determination and we need to privilege the pan-Ethiopian identity while also accommodating ethno-national identities.”

“I’m daring to dream – as I did in my first paper on this issue in 2005 – of a Northeast African Confederation,” he concluded.

Michelle Galloway: Part-time media officer at STIAS

Photograph: Noloyiso Mtembu