Asking tough questions about the origins, development and future of universities in South Africa

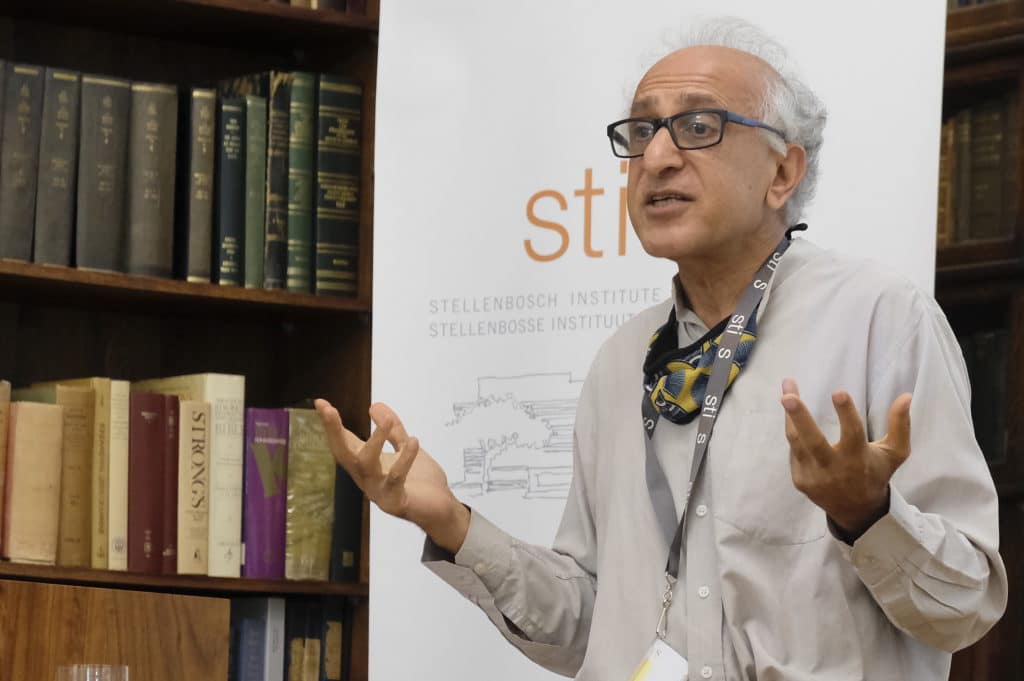

“What are South African universities for? What should be their purposes, functions, goals, roles and objects? The question is forward-looking: it concerns South African universities, rather than what have historically existed – universities in South Africa but not wholly of South Africa or for the vast majority of South Africans,” said STIAS fellow Saleem Badat of the Humanities Institute, University of KwaZulu-Natal. “If the question is not to be entirely abstract and speculative, it must proceed from historical and contemporary realities, without entirely making a virtue of those realities. Ideas about South African universities, their purposes, functions, goals and roles, their institutional character and their forms cannot assume a tabula rasa.”

Badat was presenting a seminar on his book project which he described as “an historical sociological investigation” of the origins and development of universities in South Africa through a focus on their purposes, functions, goals and roles since colonialism to today He hopes that such a history can show why it is proving so difficult to transform universities in South Africa. His interest is in critical historical scholarship not policy research that seeks quick, elegant and immediate policy solutions. He wants “to illuminate the possibilities of the transformation of universities but also the constraints the limits.”

“Right now we have replicas, often pale imitations and mimics of colonial and European institutions. Universities in but not of South Africa.”

“We need to create new South African universities taking our point of departure what exists. The great African revolutionary Amilcar Cabral emphasised that we must proceed with our feet firmly on the ground, from what exists. Historical sociologist Philip Abrams too emphasised in 1982 that the past more than just ‘provides a background to the present’, it is the basis on which people ‘struggle to create a future’; and it ‘is not just the womb of the present but the only raw material out of which the present can be constructed’.”

Badat seeks to describe and analyse the purposes, functions, goals, roles and objects that were defined historically for specific universities in South Africa, different groups of universities (‘historically white’, ‘historically black’) and for universities in South Africa more generally. The questions include: How and by whom were the purposes, functions goals and roles defined? What conditions and ideas shaped the definitions? How did the definitions change over time? To what extent, in what ways, and why did the actual pursuits of universities differ from the stated ones?

“I’m raising the questions of whose purposes and goals those were, how they were constituted, how they were shaped by time, place and space and how and why they may have changed,” he explained.

He proposes to examine these questions across four periods – colonial (1652-1910), segregation (1910-1948), apartheid (1948-1994) and post-1994.

Within these periods Badat intends to analyse the structural and conjunctural conditions in the economy, polity and society, the prevailing intellectual and scientific milieus and the thinking, human agency, conflicts and contestations that shaped universities.

“I hope to explain the origins of university education during the colonial period, how it developed during segregation and the birth of new universities under apartheid and post-1994. To explain how, in what ways, to what extent and why they have changed and with what consequences. This means focusing on both continuities and discontinuities.”

He says that “we also need research on higher learning and higher education before the advent of colonialism in 1652 but that important research is not part of this project.” The book will also focus on universities rather higher education overall.

Time and place

“Partly framing my investigation is that universities exist in a time and place – place is critically important.”

“The ideology, economics and politics of the different periods shaped universities,” he added. “They are a product of the interplay of economics, politics and social conditions. However, institutions exist in our heads too – they are not just out there.”

He explained that colonial higher education after 1652 began in the Cape in 1829 as an offshoot of secondary schools and that the University of the Cape of Good Hope (which later became the University of South Africa) was established in 1873. By 1994 there were 36 universities and technikons. This was reduced to 23 in 2004, now there are 26.

“But even those created post-1994 cannot be said to be South African,” he said. “They demonstrate great continuities with previous universities in their character and approach.”

Badat hopes to demystify some of the myths and legends about universities. “Universities were from the outset involved in professional training sought by external stakeholders (like Popes and Kings). They were never entirely ‘ivory towers’, an idea to which some seem to want to cling. They are not pristine but not entirely grubby either. They are suffused with paradoxes and contradictions. We need to engage informed by history, not on the basis of invented myths.”

He believes that we have to delve into some of the inconvenient truths about the roles universities they have played in our history and undertake empirical research to fully understand where the actual differs from the stated – “where realities doesn’t flow from the legislation, policy texts and good intentions”.

Looking at the complex, practical, day-to-day organisational processes and minutiae is also important. And in this regard, Badat will explore questions like what is expressed through the names of universities, the names of buildings, the logos and rituals of institutions, how the vision and mission statements distinguish universities from one another, and what distinctive cultures, values, traditions and norms characterise them.

While there is a lots to be learnt from the past, a concern with the present and future is strongly present. “How do we become South African/African universities, what should be their particular configuration of purposes, functions, goals and roles as appropriate to place, space and time while also being part of of a global system of knowledge dissemination and creation”.

“I see a diverse audience for the book, including scholars, scientists, intellectuals, activists, policy makers and state officials,” said Badat. “It’s not purely an academic exercise but also an intervention in the discourse on how we conceive universities. I hope that it contributes to asking what is and is not valued, and the debate around institutional transformation and decolonisation.”

And this includes asking tough questions about who should attend universities, who should teach and research, what should be taught and who should manage and govern.

In considering universities, Badat says that “we must avoid three traps. One is essentialism, which is to accord unvarying purposes, functions, goals and roles to universities across time, place and space.

At the same time “to imagine that we can apply the term ‘university’ to any kind of institution is to succumb to the trap of relativism. The final trap is that of universalism, the idea that universities everywhere must be identical to or replicas, mimics and clones of modern European universities. This way of thinking abstracts universities from place and space.”

He is critical of European epistemology and its Eurocentrism, which Immanuel Wallerstein noted in 1997 was “constitutive of the geoculture of the modern world,” and powerfully shaped “science and knowledge in universities everywhere.”

He credits Edward Said for demonstrating how European claims to normative universality function to simultaneously erase its particularity, how such claims are in Gyurminder Bhambras (2014) words “sustained through the exercise of material power in the world” and “the ways in which relations of power underpin both knowledge and the possibilities of its production.”

For Said (2004), Eurocentrism impeded human understanding because “its misleadingly skewed historiography, the parochiality of its universalism, its unexamined assumptions about Western civilization, its Orientalism, and its attempt to impose a uniformly directed theory of progress all end up reducing, rather than expanding, the possibility of catholic inclusiveness, of genuine cosmopolitan or internationalist perspective, of intellectual curiosity.”

In the rich discussion, Badat addressed the language issue; challenges in balancing funding needs with goals; research at the expense of teaching; the history and teaching of science; erosion of academic freedom; academic ranking systems; the role of African intellectual refugees; and, the crucial need for a focus on global public-good issues.

“The country has evaded the language question. We should be aspiring to teach at least in IsiXhosa, Zulu and Sotho but it’s a political minefield and at least a 50-year project. We haven’t had the courage to take the decision. Right now we are not providing epistemological access to all –the language issue is critical.”

“And,” he added, “we can learn from Afrikaans – what Mahmood Mamdani terms a decolonial language – which was created through a powerful cultural movement.”

“Stated goals and actual activities may sometimes be contradictory and paradoxical. For example, public good not private good is what universities are meant to be about but it can be difficult when you chase income from contract research. The head of a multinational can write a $1 billion cheque, a trade union can’t. There is a creeping privatisation happening and this means the agenda of the state and business predominates. We must be alert to the paradoxes and contradictions and ask what and who we are serving?”