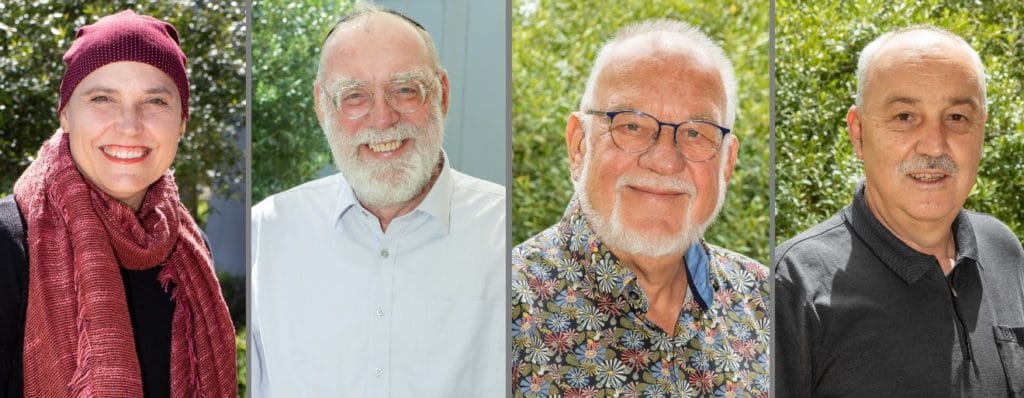

The STIAS 2021 seminar programme opened with a seminar by the ‘Gandhi research group’ comprising Wolfgang Palaver of the Department of Systematic Theology at the University of Innsbruck, Louise du Toit of the Department of Philosophy at Stellenbosch University, Ephraim Meir of the Department of Jewish Philosophy and Kabbalah at Bar-Ilan University and Ed Noort of the Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of Groningen. The group fittingly closed the first semester with a retrospective on developments within the project during their time at STIAS and some reflections on Gandhi’s ideas in current conflicts.

The project overall engages with Satyagraha and the concept of non-violence from different angles and theoretical perspectives in an attempt to understand what these ideas can bring to our world today. Immediate outputs include a special issue of the online journal Religions, on ’Non-violence and Religion’, due to be published in December this year.

The group members focused on their specific areas of study in a wide-ranging seminar.

When Gandhi meets Augustine

“The Indian Hindu (1869-1948) and the North African bishop (354-430) both refer to 2 Corinthians 3:6 ‘the letter kills, but the spirit gives life’ as a hermeneutic tool for handling religious principles and authoritative texts,” said Noort. “This thread enables Gandhi to use scriptures of different religions and allows Augustine to differentiate between opportunities and limits in his quest for truth.”

“Both Gandhi and Augustine experienced a decisive turn in their lives in their 30s and dedicated their lives to the search for truth as they understood it,” he added. “Both transformed the beliefs of their youth in decisive ways.”

Noort pointed out that for Gandhi there was an inseparable bond between faith and political actions. Equality of all religions was extremely important and an absolute requirement to create unity among Muslims and Hindus in the struggle against racism and colonialism. This struggle needed a method and Gandhi developed his non-violent interventions through what he called Satyagraha, the ‘soul force’ as an active being on the way with and to Truth as the vanishing point on the horizon and ahimsa (love, non-violence) as the instrument to move forward on that way.

Gandhi claimed the right of the later interpreter to add meaning to Holy Writ. Sense and meaning had to be developed in changing times and situations. There is no golden key above time and place, but in a concrete context texts have to stand the tests of truth, ahimsa and reason inspired by a living faith. Scriptures that promoted untouchability or violence could never be Holy Writ. Relativisations are needed when reading scriptures. However, when there was the need for a basic creed of all Hindus Gandhi could recite the first mantra of the Isha Upanishad with absolute authority because it was sufficient in summarising the entire Bhagavad Gita.

“Historicity was not that important to Gandhi,” explained Noort. “The message exceeded the persona, even if Jesus had not existed, the Sermon on the Mount would still be true.”

“Gandhi’s use of scripture demonstrated a remarkable freedom, an awareness of historical distance, a denial of exclusivity, the use of leading principles over isolated passages, and the need for figurative understanding.” Augustine similarly highlighted the difference between a literal and figurative reading of religious texts and the need for awareness of geographical, cultural and historical diversity. “He highlighted the idea of historical distance – what may have been appropriate in the past may be judged differently today.”

“If Gandhi had met Augustine he would have applauded his awareness of historical distance in scriptures. For both the Sermon on the Mount that related to doing to others as you would have them do to you was the limit of free interpretation.

“In the long line of Christian interpreters Gandhi would be even more attracted to the first chapter of the Didache,” suggested Noort, “because it is an instruction for early Christians and their daily life similar to the Sermon on the Mount.”

Gandhi in South Africa

During their time in South Africa the group undertook a field visit to explore and contextualise the work. This included visiting the first Ashram that Gandhi created in Phoenix, Durban. They were also able to meet Ela Gandhi, granddaughter of Gandhi, Member of the South African parliament (1994-2000) and well-known South African peace activist.

Palaver focused specifically on Gandhi’s time in South Africa, his contact with John Dube (founding president of the South African Native National Congress, which became the African National Congress in 1923), his ongoing conflict with Prime Minister Jan Smuts, and the influence of all of this on his ideas on non-violence.

“Gandhi was not entirely free of racial prejudice when he came to South Africa,” said Palaver. “He was influenced by Dube in moving towards ending his own prejudice and Dube, in turn, came to appreciate Gandhi’s ideas of a non-violent response to racial discrimination.”

“Nelson Mandela said in 1995 that the African struggle is rooted in the Indian struggle referring to the profound influence that Gandhi and Dube had on each other.”

The conflict that developed between Indians and Europeans in Natal, South Africa, in the early 1900s shaped Gandhi’s life and contributed to his understanding of Satyagraha.

Smuts, who was Gandhi’s main opponent, viewed this as a ‘conflict of civilisations’ rooted in cultural differences. “While recognising the differences between the Western and Indian cultures, Gandhi criticised Smuts’ position as hypocrisy supported by pseudo-philosophical arguments – seeking a justification that masked selfish enrichment and racism,” explained Palaver.

“Gandhi instead referred to ‘trade jealousy’ when he described the roots of the racial differences in Natal and saw the evoking of religious or cultural oppression to explain conflict as a diversionary tactic.”

“However, Gandhi also understood that a violent response would only prolong the rivalries.”

“His understanding of non-violence is about fighting injustice without succumbing to the temptation of violence. Satyagraha is an active force that must not be confused with passivity. It’s not about cowardice.”

“Gandhi’s reading of the Sermon on the Mount convinced him that there was nothing passive about Jesus. He underlined the active non-violence he recognised in Jesus. Jesus offered a third way to fight or flight, by opposing without mirroring. Christians today are influenced in this understanding of Jesus by Gandhi.”

Non-violence as embodied performance

Du Toit is examining Gandhi’s understanding of Satyagraha as an active struggle through the lens of feminist political philosopher Judith Butler’s understanding of non-violence as a kind of embodied performance. This lens emphasises discursive meaning, relationality, precarity and public assembly as aspects of non-violent resistance.

Butler published The Force of Non-Violence in 2020 which Du Toit uses to set up a conversation between Butler and Gandhi, in particular with respect to the ontological roots that both thinkers believe underlie the imperative for non-violent change.

“It’s interesting that Gandhi and Butler share so much,” she said. “Butler is a post-modernist feminist. They have very different ontologies but both support non-violence as the only effective solution to longer-lasting, comprehensive social change. Both see violence as something that will backfire. This line of thinking also has empirical backing from other scholars.”

She explained that Butler and Gandhi both understand that if you respond with violence to violence there is no logical end and that something radically different is needed to disrupt the logic of mutual hostility. Violence attacks the living bonds of human interdependence, while non-violent resistance holds on to the indispensability of human interdependence.

“Butler suggests we should investigate Satyagraha more closely as an embodied practice and meaningful action,” she said. “Like Gandhi she emphasises non-violence as an active principle that is clearly distinguishable from violent force.”

Gandhi has a spiritual ontology underlying his commitment to non-violence and Butler has a social ontology underlying hers. Du Toit explained that Gandhi believed Satyagraha – translated variously as life force, truth force or soul force – is natural and constantly working in the background; without it, the human world will disappear. “For Gandhi the world is based not on the force of arms but on the force of truth or love and violent change is an ineffectual short cut rooted in a lack of faith.”

“History then becomes a record of the interruptions to this force of love,” she added.

Butler’s social ontology entails that all aspects of the human world are thoroughly socially constituted, so that she can claim, “there is a sense in which violence done to another is at once a violence done to the self, but only if a relation between them defines them both quite fundamentally”.

“Both [thinkers] see all humans as social constructions – we are socially shaped beings, influenced by prevailing norms. Our selves exist within the social space in which we are formed. We are all formed by knowledges, discourse, power relations. Nobody stands separate from these constructs.”

“The social world is composed of mutually interdependent relationships,” she continued. “The force of love transforms the person of the non-violent resister, the community in whose name the resistance is performed, but also the relationship between the oppressed and the oppressor. The truth force or Satyagraha transforms the political opponent and changes systems of oppression.”

For Butler agency, ethics and freedom are possible because we can consciously choose to oppose the dominant norms that are embedded in bodies, institutions, and discourse. Norms only have power in so far as people perform them and cannot persist unless docile bodies enact them.

“You can always resist, and by no longer being docile, obedient bodies, we can start to change the scripts. This is where the potential for social change lies – when we are no longer playing by the rules.” Gandhi similarly said, “We cease to play the ruled”.

Interreligious theology and the challenge to current conflicts

“Gandhi’s Satyagraha contributes to interreligious dialogue and theology,” said Meir. “His active non-violence is a challenge for Israel and Palestine today.”

‘Gandhi’s religious thinking was amazingly inclusive,” he continued. “He was open to all religions – seeing religion as a tree with different leaves all rooted in God.”

“At the same time, he was conscious that no religion was perfect and distinguished between organised religion and religion of the heart. He saw truth as the presence of the divine in everybody and everything, and religion as a mode of interpretation of one truth. He recognised that the concept of truth is relational.”

“He found the core of non-violence across various religious texts.”

“Such interconnectedness is central in interreligious theology,” added Meir. “And if religions are only perspectives then interconnectedness is more possible.”

“Recognition of the other is a pillar of present-day interreligious theology and the concept of truth as relational is a remedy to absolute truth claims by any one religion. I believe that religious peace activists are inspired by Gandhi who interpreted religion as a non-dividing, uniting force. The notion of truth in proximity to others contains formidable potential for peace activists. Satyagraha is a challenge for the present.”

“I believe that in Israel and Palestine today Gandhi would plead for co-existence of a Palestinian State alongside an Israeli one. He would adopt a pragmatic stance and suggest the purity of compromise. He would oppose the violence and disapprove of fanatic nationalism, hatred and demonisation by either side.”

“In Israel and Palestine we should not stop caring for social cohesion,” he continued. “The parties involved should stop blaming the other and instead approach the other as a real partner with whom co-existence is possible and necessary. Self-interest must be transcended for the liberation of all.”

“Active non-violence is a courageous alternative. Violence and injustice have to be actively resisted,” said Meir. “Religious reconciliation could bring about more peaceful co-existence. In an endeavour to create a new we, we may become present for each other, assist and serve each other, pray, fast and march together. As Gandhi said, we need to be the change we want to see.”

Michelle Galloway: Part-time media officer at STIAS

Photograph: Anton Jordaan