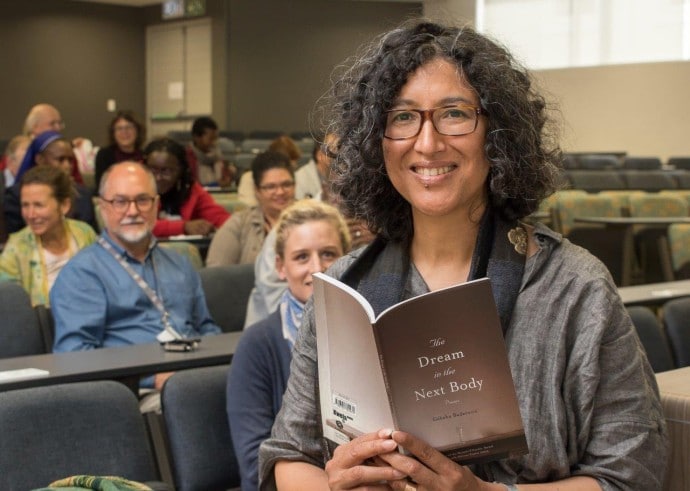

“I started to write poetry late in life. Now 18 years later the sense of being a terrified beginner has not left me,” said Prof. Gabeba Baderoon, Associate Professor of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Pennsylvania State University and STIAS fellow, who presented a poetry reading from her current work Axis and Revolution.

“While at STIAS, I’ve been immersed in a ferment of words, reading verse from all over southern Africa and the world and being entranced by the poetry of conversation over meals and among the fellows. In my office, I’ve been listening to poems in isiZulu, Sesotho and isiXhosa, pouring over translations, talking to poets. The breath of so many writers is in my ears. From them has come the inspiration for new poems,” she said.

This is her fourth poetry collection and will be published by Kwela. Baderoon co-directs the African Feminist Initiative at Pennsylvania State University and is also an Extraordinary Professor of English at Stellenbosch University. The poems she read encompassed very personal depictions of love and betrayal, her family and home, fishing and diving, and the power of photographic images. She even included “a tender poem” about government officials based on a recent experience of renewing her driver’s licence.

“Poetry allows you to say what you cannot utter,” she said.

“Poetry also does something unusual. It makes time collapse. I can’t tell you how often poetry has helped to close the distance across thousands of kilometres and several time zones.”

She added though that poetry is not about pretty words. “As a literary scholar it took me a long time to understand that. Part of my mind had to learn what it meant to write poetry. Only eventually – through my teachers – I learnt that poetry is not about making words attractive. It’s about remembering when words do something you cannot forget.”

“Words do something you cannot forget when you are hurt, and when you are overhearing a conversation that you shouldn’t have which teaches you about that person and the world.”

“Poetry happens all over,” she continued. “One of the most poetic lines I’ve ever read was scratched into the back of the plastic seat of a Golden Arrow bus that I read in the 1980s when I was attending university.”

“Poetry is not always pretty but sometimes it brings us close to beauty.”

“I’m going to share some of the work that has come from 18 years of trying to understand that mystery,” she added.

She started by speaking of her early years in Athlone. “I’ve thought about home a lot in the past six months living in Stellenbosch and at weekends going back to the house I grew up in in Athlone where I lived for 28 years.”

“Athlone was a strange place to grow up in,” she continued. “My family arrived in Athlone as a result of the forced removals in South Africa. So the 28 years in which I had grown the deepest, most solid roots in a place coincided with the time that my mother’s sense of home was abruptly cut off. I learnt to understand that home could be both real and ghostly. Writing opened up that vision and perspective for me. Writing about leaving home was to discover what home was.”

Speaking about her poem Old photographs she said: “When I think about that poem I think about how you don’t really know the person you love. And how grateful you should be to the people who loved them before. And I think about the ways in which women, when they are heterosexual, are expected to compete with one another for men. I always thought I would be very good friends with my partner’s former lovers. In some ways it’s as much about her as it is about him.”

She described I forget to look as “a poem about my mother and how she became a doctor”.

“When I arrived at UCT 30 years ago I felt so not at home but the fact that my mother had been there allowed me to walk in that often inhospitable space and feel I had a right to be there.”

When asked about the audience for her poetry she replied. “I started to write poetry when I was taken away from everything familiar. I took an evening class in 1999 a month after leaving South Africa on a fellowship. A few days before I left, my father died. That sense of disjuncture and tearing away was the birth of poetry for me. I was writing to all of those absences.”

“Because I had no idea I was writing so that other people could read it I didn’t have a sense of an audience at the beginning. I could fulfil the thoughts in my head without thinking of the broader resonances and usefulness. Being set free from a sense of obligation to an audience has been good for me. Although in the broader sense I care very deeply about representing South Africa, addressing questions of race and injustice and politics – all of those things are part of what I think of as necessary for thinking and being in the world.”

“I don’t think of myself as writing specifically to a South African audience,” she added. “I think of myself as writing about a situation that is intricate and complex, and sometimes difficult. Whoever reads it has to do the work of receiving that difficulty and intricacy. It is possible to read difficult things and be enchanted. That enchantment should be what people bring to reading African poetry as well.”

Breaking silences

When asked about the dangers of being so open and transparent she replied: “Only our generation knows what that means these days. For post-colonial writers the extent to which writers render themselves transparent is almost a mark of authenticity. However, we risk turning our lives into currency. For a long time I tried to write in a way that hid the details about myself and the people near to me who had helped me see the world in a new way. But that kind of obscure, opaque writing was useless – useless to me, useless to anybody, useless to the people I was protecting. I decided I wouldn’t try to protect people or myself as long as the writing wasn’t trying to make currency or exploit a situation. If I felt there was something unsaid for a long time out of a sense of pain or shame or ‘unspokenness’ that had to do with pressures I refused to accept, then I would break the secrecy.”

“But it’s a delicate line. I recently wrote a poem about sexual assault where I had to decide on the boundaries – what I would protect and what I would not protect,” she continued. “That’s a topic that often when we observe the silences we sustain the trauma for our culture at large.”

“It has to be negotiated – every time anew,” she added.

“Language does remarkable things and even when we think it betrays us it can also be doing something else. I’m hoping it won’t fall on the side that is betrayal but that it won’t also fall on the side that is utilitarian and exploitative. I navigate that all the time.”

When asked about poetry in the post-truth world, she replied: “I recently spoke to two directors of projects on post-truth who were focusing on journalism and science. I asked where was the literature and the poetry? Imagination brings us crucial insights about how difficult truth is and also that truth comes to us in language that causes us to focus on one perspective and exclude others.”

“Imaginative work asks us to reflect on why we are looking here and not there. It allows us a powerful, evocative way to look at the grounds for understanding what truth is. I think poetry has a very important role to play but there is also risk – poets are not soothsayers – anybody unquestioned is in a dangerous situation. But poetry and other creative arts should be alongside truth-telling areas like science and journalism and all the other ways in which we reflect on the complexities of the world.”

“History is one of the ways in which we remember the past but history is full of erasures. It’s the novelists, playwrights, singers and poets who have drawn attention to these absences. The truth that has been validated through discourses we respect has been completed by the practices of creativity. They must live together.”

Words: Michelle Galloway, Part-time media officer at STIAS

Photographs: Christoff Pauw & Anton Jordaan