(A link to Breyten Breytenbach’s keynote address at the book launch appears at the bottom of this page.)

The responses to the January 2015 looting of foreign-owned shops in Soweto and in April in Durban’s central business district and elsewhere reveal more about the South African national consciousness than the events themselves. The ritual condemnations; the initial denial of xenophobia in preference to labelling it criminality; blaming victims and convoluted excuses of perpetrators are almost worse than the official silence and long-standing passivity about well-known xenophobic attitudes. When the President insists that “South Africans in general are not xenophobic” , he ignores all surveys (Afrobarometer) showing a vast majority distrusts (black) foreigners, wishes to restrict their residence rights and prohibits the eventual acquisition of citizenship.

On these scores South African attitudes are not unique. Anti-immigrant hostility inflicts most European societies. Perhaps suspicion of strangers is even universal: preferential kin selection as an evolutionary advantage, as sociobiologists assert. . What is uniquely South African is the ferocious mob violence against fellow Africans. Why? The structural violence of apartheid laws has continued in the post-apartheid era for many reasons: the breakdown of family cohesion in poor areas which no longer shames brutalized youngsters; loss of moral legitimacy by government institutions, particularly a dysfunctional justice system; violence was glorified in the “armed struggle”, but, above all, marginalized slum dwellers learned that they only receive attention when they act destructively. Despite a rule bound constitution for conflict resolution, in a representative survey (Afrobarometer) 43 percent in the Western Cape agreed with the suggestion that “it is sometimes necessary to use violence in support for a just cause”.

Only after two weeks of denial did the government acknowledge the emergency in response to business repercussions in the rest of Africa and the deteriorating image of the country abroad. In 2014, the former South African Ambassador to the US, Ebrahim Rasool, at the US-Africa Leaders Summit, declared South Africa “a moral superpower”, able to teach the world the way Nelson Mandela managed conflict resolution. In this view, liberated citizens cannot be xenophobic if the image of a glorified rainbow nation is to be salvaged. Admitting racism toward fellow Africans would deprive the ruling party of the moral high ground. The belated recognition of xenophobia, unanimous condemnations of violence and noble solidarity marches reinvigorated civil society organizations, but will not change attitudes on their own. That South African political exiles were welcomed in African countries in the past hardly impacts a generation with a limited historical consciousness .

Most media explanations of these hate-crimes are far too rational to grasp underlying psychological causes. The very presence of thriving Somali shops insults unsuccessful, impoverished township dwellers. They endure daily exposure as failures. Envy breeds resentment. Perceived humiliation fuels scapegoating. Low self-esteem searches for enhanced identity. Powerless people empower themselves by attacking those below them. While the ruling elite enriches itself by looting the state, the forgotten slum dwellers claim their share by collecting the crumbs from the vulnerable amakwerekwere. The derogatory label this time included not only other Africans, mainly Somalis, but Pakistani and Bangladeshi informal traders as well. Sensitive scholars like Francis Nyamnjoh already hint that the “bizarre nativity game of exclusionary violence” could easily expand from “outsiders within” to longtime insiders, such as Indian South Africans, Coloureds and lastly whites. Retribalization, relatively successfully contained by the ANC and SACP in public discourse, nevertheless simmers under the surface. The more meagra the pie in an economic downturn, the more a negative solidarity of ethnic nepotism comes to the fore. At an ANC conference about the nomination of the next president, delegates proudly wore T-shirts with the inscription “100% Zulu Boy”. During apartheid anybody in tribal clothing was ridiculed among the progressive movement. Nowadays influential traditional leaders in leopard skin can incite xenophobia without officially being called to order.

Hunger and poverty do not drive frenzied youngsters to rob stores or stab their owners. Drug addiction does. Most looters own cell phones and stealing vouchers for airtime was a priority. The breakdown of family cohesion in mostly fatherless township households has eliminated shame and neutralized moral inhibitions. Overburdened mothers, often without maintenance payments by the absentee fathers, are unable as sole breadwinners to provide the emotional intimacy and security needed by youngsters. Gangs function as family substitutes and identity enhancers. Underqualified township teachers have utterly failed to instill political literacy to comprehend global migration. South Africans of all hues cultivate an exceptionalism of being in Africa, but not of Africa. New comers from the alien, dark continent are not to be trusted. Well qualified foreign science and mathematics teachers could function as role models, besides raising standards. However, the teachers union (SADTU) does not welcome cosmopolitan non-nationals in its ranks, let alone being lectured on political education.

Competition for jobs by unemployed youth amounts to a cliché. Looting school children are not yet in the job market. Neither does alleged inequality between foreigners and locals explain the antagonism. Somali tenants mostly start from scratch with loans from relatives; they frequently employ locals; they extend credit to customers and pay rent on time. But they work longer, harder and sell cheaper, due to a small profit margin and “collective entrepreneurship”. Self-hate by the locals fuels envy of the successful foreigners. In economic terms, all immigrant societies around the world have benefitted from the skills and hard work of newcomers. However, such rational reasoning does not persuade losers in the competition for scarce resources, perceived as a zero-sum game.

Why can’t locals emulate the foreigners and learn from them? Why can’t they also buy wholesale and introduce smaller mark-ups? ‘We don’t trust each other’, answered many local respondents in our research. In an atomized space of marginalized people, mutual trust of responsible citizens amounts to a delusion. The very notion of community is problematic. At the most, an exclusionary solidarity exempts local shops from being looted, but not equally poor blacks from outside being attacked.

Some pundits have criticized ‘Home Affairs’ for extending work permits to Zimbabweans, when so many locals are unemployed. Not only are the foreigners preferred by employers, because they go the extra mile, but how else could they survive when they have to fend for themselves? Pretoria should be criticized for supporting a tyrannical regime in Harare, not for easing the burden of their escapees. In contrast to the migrants in Europe, most Zimbabwean refugees would return home, if conditions were to improve. The height of hypocricy is the Mugabe criticism of the South African government for failing to protect the 2m Zimbabwean nationals who would not be in South Africa without the chaotic economic policies and violent rule of ZANU.

A sad indictment in the xenophobic drama must be reserved for the police management. The commentator of City Press (01/02/2015) Justice Malala cites incontrovertible evidence: “The police, in large numbers, are aiding, abetting and even partaking in the looting”, but mostly looking away. Malala quotes a story of police, ordering people to queue up to “loot in an orderly manner” by entering a shop four at a time. However, police merely reflect the attitudes of the population at large. Their training has not incorporated any lessons from the 2008 xenophobic outbreaks. While police attitudes should not be generalized, corruption and disrespectful behavior of cops on the street has been confirmed in many of our interviews and also established in an official inquiry in the Western Cape (O’Reagan/Pikoli Khayelitsha Police Commission, 2012-2014).

Victim blame abounds. Ignoring the attacks against foreigners in January 2015, Home Affairs announces that their legal status would be investigated. However, not being harmed or treated inhumanely is an absolute right that does not depend on the person’s citizenship. Adding to the moral panic around outsiders, a ruling party leader blamed weak immigration laws and their potential to give rise to terror organizations, such as Boko Haram. A cabinet member insisted on foreigners “revealing their trade secrets” as a precondition for being allowed to operate. Barring groups from certain activities on the basis of their ethnic origin violates the South African constitution. The humiliating treatment of refugees by Home Affairs officials in the renewal of permits reinforces for an already suspicious population the need to guard against outsiders. Taxi drivers tell you a widely held belief that most crimes are committed by foreigners. Yet the government has never published statistics about national and non-nationals convicted.

Compared with the dramatic rise of xenophobia in Western Europe, South Africa originally differed in two respects: First, in Europe antagonism against foreigners is mobilized from above by populist demagogues; in South Africa the resentment originates from below and is condemned by all political parties as ‘shameful’. Surprisingly, no anti-immigration party exists, but all politicians advocate stricter border controls. No Marine Le Pen has yet emerged in South Africa. However, the schizophrenia of feeling embarrassed by the xenophobic label and simultaneously playing to the xenophobic gallery, particularly at the local level, does not rule out a gradual nativist shift. The Apartheid government restricted Indians from settling in the Orange Free State; Idi Amin expelled their counterparts from Uganda and the African Union elected a nationalist Mugabe as their chair in 2015. Who can guarantee that the South African rainbow does not dissolve similarly?

A second difference to wealthy Western Europe is the absence of large scale slums in which abandoned locals compete with foreigners for retail space. European xenophobia focuses mainly on identity issues , not on meager means of survival through spaza shops. Yes, German taxpayers resent that asylum claimants receive the same social benefits as citizens, but this does not affect their own secure livelihood. European state authorities would not passively tolerate the South African violence. However, given a prejudiced electorate in both Europe and South Africa, political parties would lose voters if they resolutely take the side of victimized outsiders. In both contexts parties confront the choice between morality or pleasing their voters.

A related difference to Europe allows more optimism. Islamophobia and anxiety about an incompatible religion plays no role in South Africa. Whatever motivates the animosity toward Muslim Somalis, religion has never featured. Unlike Europe, Muslims are not attacked for undermining an entrenched homogeneous culture. The South African divided society has long learned to co-exist with diversity. That is the main hope to overcome xenophobia.

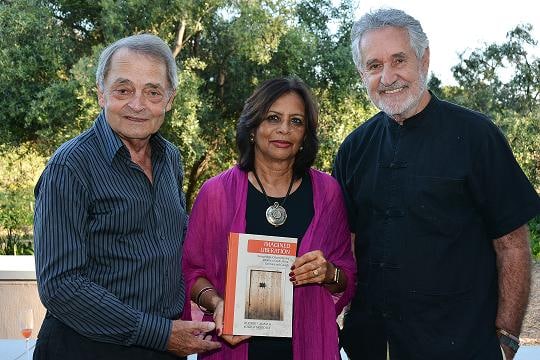

Heribert Adam and Kogila Moodley are sociologists from Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, and were resident STIAS fellows in 2012 and 2013. The results of their STIAS project were published as

Imagined Liberation: Xenophobia, Citizenship and Identity in South Africa, Germany and Canada

Heribert Adam and Kogila Moodley

SUN PRESS (2014, 246 pp) ISBN: 978-1-920338-98-5

Imagined Liberation @ Africansunmedia

An expanded edition is forthcoming with Temple University Press in Philadelphia from which some of the arguments in this essay are drawn. Contact: [email protected] or [email protected]

Breyten Breytenbach’s keynote address at the book launch of Imagined Liberation, The Topos and the Topography of Utopia, can be read here.